The coronavirus pandemic and new requirements in Republican-led states have created voting obstacles for college students this year. Yet youth participation in the American election appears to be on the rise.

By DAN LEVIN

The New York Times International Edition, 31 October 2020

With many American campus quads resembling ghost towns and childhood bedrooms serving as lecture halls, politically active college students have moved their get-out-the-vote efforts online, hosting debate watch parties on Zoom, recruiting poll workers over Instagram and encouraging students to post their voting plans on Snapchat.

Young voters, traditionally a difficult group for politicians to get to the polls, are showing rare levels of enthusiasm in this election, even as college students have faced new obstacles to casting their ballots — some stemming from the coronavirus pandemic, and others from elected officials seeking to impede college voting.

At Bard College in New York State, students sued to bring a polling station to campus. Residential advisers at the University of Pittsburgh used Zoom to register new voters. And at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, students have signed up as poll workers to help their fellow Badgers navigate some of the nation’s toughest voter identification laws.

“We’ve had to exhaust every possible option to continue energizing voters,” said Roderick Hart, a junior at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

“In the past, we had massive rallies and all these people walking around with clipboards registering kids to vote,” Mr. Hart, 20, said. “But now, social media is really our only way of connecting everybody at once, considering we’re not on campus.”

Despite the difficulties, efforts to mobilize the youth vote, along with greater accessibility through early-voting hours and mail-in ballot options, appear to be paying off, with potentially significant implications for races nationwide.

More than five million voters under 30 have already cast ballots for the Tuesday election, including nearly three million in 14 key states that could decide the presidency and control of the Senate, according to data compiled by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University. That is more than double the number of ballots cast by young voters at a similar point in the 2016 presidential election, mirroring an increase in early voting among all demographics because of coronavirus concerns. The early-voting numbers for young people are particularly notable in states such as Texas, where, by a week ago, nearly two-thirds as many had cast early votes as the total number of young voters four years ago, according to Tufts researchers.

A national poll conducted by the Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School found that 63 percent of youth voters surveyed said they would “definitely be voting,” suggesting turnout similar to 2008, when enthusiasm for Barack Obama’s candidacy led to higher levels of youth voting than in any election since 1984.

Energized by issues like climate change and the Trump presidency, college students emerged as a crucial voting bloc in the 2018 midterms, when their turnout rate of 40.3 percent, according to the Tufts Institute for Democracy and Higher Education, was more than double the rate four years earlier.

Faced with those surging numbers among a voting group that leans heavily Democratic, Republican lawmakers in numerous states, including several battlegrounds, have taken actions that they said were intended to prevent voter fraud — including enacting restrictive ID rules and byzantine voter registration requirements — that have also made it more difficult for college students to cast ballots.

Elected officials have also moved to diminish the electoral power of campuses through redistricting, as well as by limiting early voting sites, purging voter rolls or refusing to permit polling stations on campus. And the logistics of the pandemic could alter where young people cast their ballots, potentially affecting races where candidates, typically Democrats, count on support from students living in their districts — but many of those students are now at home.

“Every aspect of students’ ability to vote is under attack,” said Maxim Thorne, managing director of the Andrew Goodman Foundation, a nonprofit group focused on protecting voting rights for young people. “You have to fight these battles on every front, whether you’re in a state as blue as New York or as red as Georgia.”

In New Hampshire, where six in 10 college students come from outside the state, a rate among the nation’s highest, a Republican-backed law took effect last fall requiring newly registered voters who drive to obtain an in-state driver’s license and auto registration, which can cost hundreds of dollars annually. The law passed after years of calls by state Republicans to clamp down on voting access for college students.

“They are kids voting liberal, voting their feelings, with no life experience,” the state’s Republican House speaker said in 2011 when discussing plans to tighten up voting requirements.

Republicans in North Carolina enacted voter ID requirements in 2018 that recognized student identification cards as valid but proved so cumbersome that large state universities were unable to comply. A later revision relaxed the rules, and a federal judge blocked the law in December, but confusion lingers.

“The thing that’s hard is, everybody’s like, ‘ No I can’t vote today because I don’t have my ID with me,’ and you have to explain they don’t need that,” said Kate Fellman, executive director of You Can Vote, a nonpartisan group in North Carolina.

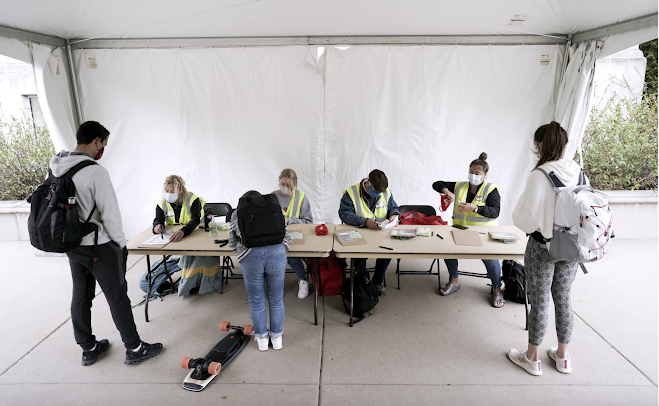

In Wisconsin, Republicans have imposed some of the toughest restrictions, including a requirement that IDs used for voting expire within two years, which invalidates most student IDs issued by four-year schools. The University of Wisconsin, which has around 40,000 students in Madison, created a second form of ID that complies with the voter law. When the pandemic shuttered campus last spring, the school developed a digital version of the voter ID, and students can now print them out at campus polling sites.

Not all colleges are so enthusiastic about ensuring students can vote. In September, the University of Georgia canceled plans for in-person voting on campus, citing concerns about social distancing and insufficient space during the pandemic.

After an uproar from student voting groups and local officials — who noted that the school had chosen to allow up to 23,000 fans to attend home football games — the university reversed course and agreed to house voting booths in the basketball arena.

At Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., students and the school sued in September to get a polling site on campus; the closest place to vote was at a church located down a dirt road in the nearby town of Red Hook.

A New York State Supreme Court judge originally denied their petition, citing a Republican member of the Dutchess County Board of Elections who said it was too close to the election to change polling locations. Yet the very next day, the board moved two other polling sites in Red Hook.

On Friday, the judge reversed her decision and ordered the polling site to be moved to Bard’s main student center.

“For the first time on this campus,” said Sadia Saba, 21, a senior who was a plaintiff in the case, “students feel like their voices are being heard in the political process.”

No comments:

Post a Comment