This blog is an online publication of words, sounds, pictures and moving images, launched to increase your exposure to the English language and/or supplement your in-person English course with language structures, challenging new readings, TED talks, trailers, quality videos, thought-provoking posts, reliable news, quotations, food for thought and icon links to related websites or to the cloud.

Friday, June 06, 2025

Living Alone Does Not Mean Living Lonely

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

B2 Advertising Techniques

Avant garde: the suggestion that using this product puts the user ahead of the times, e.g. a toy manufacturer encourages kids to be the first on the block to have a new toy.

Bandwagon: the suggestion that everybody is using the product and that you should too in order to be part of the group, e.g. a credit card company quotes the number of millions of people who use their card.

Facts and figures: statistics and objective factual information is used to prove the superiority of the product, e.g. a car manufacturer quotes the amount of time it takes their car to get from 0 to 100 kph.

Hidden fears: the suggestion that this product will protect the user from some danger, e.g. a laundry detergent manufacturer suggests that you will be embarrassed when strangers see “ring around the collar” of your shirts or blouses.

Magic ingredients: the suggestion that some almost miraculous discovery makes the product exceptionally effective, e.g. a pharmaceutical manufacturer describes a special coating that makes their pain reliever less irritating to the stomach than a competitor’s.

Patriotism: the suggestion that by purchasing this product you show your love for your country, e.g. a company brags about its product being made in Canada and employing Canadian workers.

Plain folks: the suggestion that the product is a practical product of good value for ordinary people, e.g. a cereal manufacturer shows an ordinary family sitting down to breakfast and enjoying their product.

Snob appeal: suggesting that the use of this product makes the customer part of an elite group with a luxurious and glamorous life style, e.g. a coffee manufacturer shows people dressed in formal gowns and tuxedos drinking their brand at an art gallery.

Transfer: words and ideas with positive connotations are used to suggest that the positive qualities should be associated with the product and the user, e.g. a textile manufacturer wanting people to wear their product to stay cool during the summer shows people wearing fashions made from their cloth at a sunny seaside setting where there is a cool breeze.

Testimonial: a famous personality is used to endorse the product, e.g. a famous basketball player recommends a particular brand of trainers.

Wit and humour: customers are attracted to products that divert the audience by giving viewers a reason to laugh or to be entertained by clever use of visuals or language.

Viral marketing: trying to get the customers themselves to advertise the product by telling all their friends about it on the internet.

Follow-up Exercises:

1. Can you think of one example of some of these techniques in real life? Here are three examples: ING Direct uses the bandwagon technique to get new clients. The Alimentos de Andalucía campaign appeals to consumers’ patriotism. Ferrero Rocher is a textbook case of snob appeal.

Sense8_series

- Sense8 tells the story of eight strangers played by an impressive cast of international actors and actresses: Will (Smith), Riley (Middleton), Capheus (Ameen), Sun (Bae), Lito (Silvestre), Kala (Desai), Wolfgang (Riemelt), and Nomi (Clayton). Each individual is from a different culture and part of the world. In the aftermath of a tragic death which they all experience through what they perceive as dreams or visions, they suddenly find themselves growing mentally and emotionally connected. While trying to figure how and why this connection happened and what it means, a mysterious man named Jonas tries to help the eight. Meanwhile, another stranger called Whispers attempts to hunt them down, using the same sensate power to gain full access to a sensate's mind (thoughts/sight) after looking into their eyes. Each episode reflects the views of the characters interacting with each other while delving deeper into their backgrounds and what sets them apart and brings them together with the others.This group of strangers are suddenly linked mentally, and must find a way to survive being hunted by those who see them as a threat to the world's order. They all experience a rebirth which inexplicably links them intellectually, emotionally and sensually. We are taken along their journey to discover exactly what they are going through, witnessing their interactions from face-to-face conversations from opposite sides of the world without the use of any devices, simply using each other's skills and abilities, learning about each other, all the while being pursued by a secretive group that wish to lobotomize them in order to prevent an evolutionary path they do not wish to become humanity's future. Written and directed by the Wachowski sisters, this is an un unmissable science-fiction drama series! A total visual treat. I recommend watching it with English subtitles on.

A Letter Home

Saturday, May 04, 2024

The Grindrization of Gay Identity

GRINDR, Manhunt, Gaydar, Scruff, Jack’d—for any gay man who’s been “out there” for any part of the last two decades, these websites or applications have become a familiar sight. For many men they occupy a substantial fraction of the day’s stream of experience, and for many others they form an integral part of their personal identity or sense of self.

But long before the arrival of the Internet, the social media, the hookup apps, there were GLBT people who lived, like everyone else, in what is now referred to as “real life.” I would argue that historically gay identity has always been characterized by a fundamental duality. The first identity is a response to the cultural prohibition or negation of homosexuality throughout history. This has been manifested as a lack of rights, a lack of visibility, a lack of social acceptance, a prohibition on the trappings of gay identity: sex acts prohibited, legal unions barred or blocked, blood donations refused, and so on, ad nauseam.

A second identity arose, partly in response to this repression, that stressed the value of overt visibility, of being not just quietly self-accepting but publicly out to one’s family and friends and anyone else who would listen. This is the ideal that would come to dominate cultural representations of GLBT identity for decades to come. In the late 1960s and ’70s, this concept manifested itself as protest marches, the Stonewall riots, the first pride parades, gender non-conformity in public venues, and various kiss-ins, love-ins, and so on.

Gay Liberation was all about bringing gayness into the light of day and dragging people out of the closet. But the closet never went away, and the result was a bifurcated system in which some people were “out” and others “in the closet”—wholly or in part, or perhaps in the process of “coming out.” This dynamic of “in” or “out” created a kind of existential dualism that still operates as a guiding principle of GLBT identity formation.

So, what precisely do the Internet and this age of cyber domination mean for these two polarized identities and the emerging middle-ground identity? If we were to think of an example of each type of identity outlined above, and a GLBT individual who epitomized each, we could come a little closer to imagining the cultural impact of the Internet.

Painting in broad strokes, an identity mired in a sense of prohibition could potentially be a description of a closeted gay man. The feeling of not wanting to inhabit or exhibit a gay sexual identity—and all the efforts of hiding that go with it—could be seen as a “negative space” identity. This identity would have certain hallmarks: refusal to accept a gay orientation openly, lying to close friends and family, internal struggles, deceptive practices to keep everyone in the dark, surreptitious encounters, and so forth. In the past, this may have emerged as seeking out sexual encounters in discreet and anonymous ways: outdoor cruising, for example, with its hidden and anonymous encounters. The defining feature of this negative space was the need to remain invisible: to indulge sexually but not identify as gay; to straddle two worlds without losing any crucial benefits in either of them.

In the modern era of technology, this negative space is clandestine both in the real world and now in the cyber world. The Internet allows even higher levels of anonymity than venues of the past. The classic strategy on Grindr, Scruff, et al. is to display a photo of one’s torso without a head and its all-revealing face. (A related strategy would be to display a fake face photo.) Such a user is also likely to offer very few clues that would give away his actual identity.

Considering the impact of the Internet on this negative identity, we need to keep in mind the nature of cyber reality, which is able to do two opposing things simultaneously. It offers the possibility of total anonymity on one extreme, or the potential for incredible visibility, even a kind of fame, on the other. Between these two extremes, the user’s relative anonymity or visibility can be fashioned as a (semi-)fictitious creation either way: it can act as a projection of a total falsehood or an altered version of the reality of an individual’s life. Prior to the great technological advances of the last few decades, there was no technological platform that could provide this chameleon-like ability to inhabit different identities at will. (Stage costumes were probably the closest equivalent.) You don’t like your profile picture? Use a more attractive one or Photoshop your features just a tad. Or, if you’d prefer, remain the ultimate mystery: a presence behind a screen with no visible characteristics—the alluring (and annoying) blank profile.

To move back to the “negative space” for GLBT identity, it is in the nature of the Internet to enable the closeted to operate in full stealth mode. The unprecedented success of a mobile geosocial networking application such as Grindr, created by Joel Simkhai in 2009, is testament to the fact that cyberspace has become the new haven for closeted gay men. The app was designed using geolocation technology to pinpoint other men using Grindr in one’s immediate vicinity, whose pictures and profiles appear in real time on your smartphone. This is the modern equivalent of cruising a park or restroom hoping to happen upon another like-minded individual seeking similar sexual release.

It’s interesting to note, but perhaps not surprising, that this app was pioneered by a gay man for use by gay men cruising. The straight equivalent came quite a bit later and was based upon the existing gay platforms. It’s also noteworthy that Grindr’s market was originally assumed to be closeted gay men, those who shied away from public venues like gay bars. But if it started as a “negative space” for a closeted gay identity, Grindr and its kind have gone on to become the defining feature of the gay community, the one thing that just about everyone has in common.

What this suggests is that there is also room for a “positive space” identity, which would be the individual who is out in real life and authentic in the cyber world. This individual publicly acknowledges a GLBT identity while also maintaining visibility in virtual spaces. This is usually represented by someone who publicly displays a clear face picture and is comfortable—possibly even militant—in doing so, often specifying in his profile that no one without a face pic need apply.

On that topic, a recent trend on dating and hookup apps is the ostracism of users who don’t include a face picture with their profile. And not just any face picture: it must be recent, well-lit, and free of sunglasses. (Many profiles use slogans like “If you’re faceless, I’m speechless” or “Be a man and show your face.”) Someone who doesn’t have a face pic on their profile (those infamous “torsos”) will probably be asked to provide one on first contact with another user. For this individual, the opposing forces of the two GLBT identities are at work. The need to hide and move in darkness behind a blank profile is countered by the demand for visibility, for revealing one’s authentic self. (And what is more inescapable than a photograph?) Ultimately, it’s a demand that the person “come out of the closet” in almost the old-fashioned sense.

THE SHEER RANGE of identity expressions that avail themselves to those who acknowledge their GLBT identity on some level and present themselves to the world is substantial and far-reaching. The first question is the Internet’s impact on the manifestations of these “positive space” identities. The paragon of positive identity would be the GLBT person who uses the Internet as a platform and a means of identity expression that is merely an extension of his real-life persona: the openly gay man who is out on-line and clearly displays his face for the world to see.

However, the world of virtual encounters is rarely that straightforward, and there are various means of identifying oneself that involve more layered identities. In the virtual world, participants have to swiftly alert other like-minded participants to their existence. Part of the lure of the Internet is its ability to reveal vital statistics quickly, with little left to the imagination, so as to screen out undesirable attributes and speed up the interaction. Thus a verbal shorthand has evolved to speed up the screening process. One example would be the widespread use of the phrase “straight acting/appearing” as a way to screen out those with camp sensibilities or effeminate mannerisms. While the use of these screeners can be traced back to gay personal ads in the 1970s, the cyber world makes ample use of them. Some apps have identified “tribes” that men can subcribe to—such as “Bear,” “Geek,” “Jock,” “Poz,” and so on—affiliations that become part of your identity whenever you inhabit this world. While this self-sorting method does have its efficiencies, it might also be seen as divisive, a source of exclusion and cliquishness.

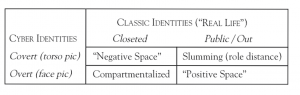

With the “pure” positions of “positive space” and “negative space”—the guy who’s out in real life and presents his authentic self in cyber world, versus the guy who’s closeted IRL (in real life) and conceals his identity, or presents a false identity, on the app—it’s time to consider the mixed positions. To understand these different groups and their cyber avatars, we need to be able to imagine four distinct positions or ways of identifying. In addition to the two consistent positions, there are two others that present a dissonance between everyday reality and virtual reality.

The first is the gay guy who is closeted or semi-closeted in real life spaces yet is quite open in the cyber world. Whereas the “negative space” identifier refused to display an accurate face picture, this person does not mind being out in virtual space. There may be high levels of deception—such as not giving away too many personal or real life details, the use of a false name, only choosing to meet at specific venues or under certain conditions—but by all appearances this guy is a star, everything you could want in a casual hookup. For such a participant, the app is a fantasy playground that’s a world apart from everyday life, and it should remain so. This individual may be heard saying, “I may be gay but it doesn’t define who I am” or “My private life has nothing to do with my work life.” There may even be a certain level of self-deception that leads this individual to believe that the virtual world and real world are further apart than they actually are, which may result in vastly different behavior in the two compartmentalized domains.

The second position is that of the gay person who’s out and proud in real life, and may even be actively involved in GLBT social and political arenas, but who doesn’t necessarily want it to be widely known that he’s active on Grindr or Scruff. When it comes to the cyber world, a certain degree of surreptitiousness comes into play. This behavior is motivated by a desire to remain anonymous in the world of virtual encounters: a certain distancing of roles occurs that is typified by secrecy on-line (a reluctance to show a face picture), versus a high degree of visibility in the real world. For this person, there may be shame in reconciling the differing aspects of his personal identity—the prominent and successful person for whom cruising on the dating apps is a kind of “slumming.” Such a person might have a desire to go incognito when on-line and engage in less wholesome activities there.

The two “mixed” identities demonstrate that, beyond pure visibility or pure anonymity, the social network allows for various permutations on visibility and on personal identity itself. How a person chooses to identify himself in this world has much to do with what he wants from it, whether a simple hookup, the faster the better, or the opportunity to play the game of hooking up, or to be on display, or just to make friends, as many users claim. Are Grindr et al. ultimately a furtive world, the Ramble in cyberspace, or is it the ultimate Panopticon, where everyone has a perfect view of everyone else? People can try to separate the two worlds, but ultimately they leak into one another, as when you spot your neighbor on Grindr or your coworker on Scruff. And, of course, hookups do take place on occasion, perhaps quite frequently, which is the whole point, after all—and the point at which “real life” gets the upper hand, and the reliability of profile pics and specs is put to the test.

At the risk of schematization, the two realms of identity formation can be crossed with the two ways of being (out versus closeted) to produce a typology with the four positions that I’ve described:

The four ideal types that I’ve suggested are formed by the intersection of real life spaces and the cyber world. The Internet allows GLBT individuals to put their identities into motion in varied and volitional ways: it provides a range of choices for how you will be identified and what version of yourself you will choose to put forward in the virtual world. The significant interplay between the Internet and GLBT culture has occurred due to precisely the duality inherent in both: secrecy versus openness, anonymity versus identity. Given the whole history of the closet and the concealment of one’s true nature, the dualities of social media encapsulate those of the GLBT community in a special and particular way. The importance of social media to modern gay identity is evident every time you sign in to your favorite mobile dating application: for better or worse, this is where much of the cultivation of personal identity takes place in the digital age.

Krishen Samuel is a writer and speech pathologist based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He can be reached at krish-s@hotmail.com.

Sunday, March 31, 2024

Para mejorar el inglés, deberíamos dejar de doblar películas radicalmente, de un día para otro

By Nacho Meneses, El País, 21 de marzo de 2024

Llamar la atención sobre los aspectos negativos de un desafío tan persistente como el aprendizaje del inglés no implica dejar de reconocer los progresos conseguidos. Por eso no es contradictorio afirmar, con una mano, que el nivel de inglés en España lleva años atascado (según el EF English Proficiency English (EPI) de 2023, no ha habido cambios sustanciales desde al menos 2015) mientras, con la otra, se hace gala de un nivel competencial de idiomas cada vez mayor en los jóvenes que se gradúan de Secundaria y Bachillerato, así como del impacto de los programas de educación bilingües en las distintas comunidades autónomas.

Por otra parte, continúa, “con las condiciones actuales, creo que se podrían dedicar más partidas a enviar niños y jóvenes al extranjero, como en la época de Zapatero, cuando hubo 10.000 niños que así lo hicieron. Y no solo por el impacto que tiene en el promedio de la sociedad, sino porque se habla mucho del tema, y se genera un debate y una concienciación absolutamente básicos para las naciones”.

Objetivo, la competencia comunicativa

Para Martí, cuya organización cumple estos días 50 años de presencia en España, parte de las causas hay que buscarlas también en factores estructurales como el hecho de que ni el inglés (ni la educación en general) son en realidad una prioridad política: “No nos hemos tomado en serio modernizar la educación; no hay un plan claro de cómo enseñar inglés y, como no planeamos de forma estratégica, tampoco se quiere medir de forma sistémica cuáles son los resultados de las inversiones que se hacen en ese sentido”, afirma.

Otro de los obstáculos que dificultan la consecución de un mejor nivel de inglés tiene que ver con la falta de oportunidades para practicar el idioma en contextos reales, además de las exigencias de la cultura de la inmediatez en la sociedad actual. “Se plantean cosas cada vez a más corto plazo, lo cual significa que no encaja realizar un curso de 10 meses para aprender un idioma... Conseguirlo requiere tiempo y constancia y hay que planificar a largo plazo”, explica David Bradshaw, responsable de Evaluación de Cambridge University Press & Assessment, antes de añadir que “la tentación de aparentes atajos en este proceso lleva a que muchas personas no alcancen sus metas”.

Fomentar la exposición al inglés desde edades tempranas es otro de los factores que puede contribuir a una mejora competencial, integrando contenido en inglés en los medios de entretenimiento: “Cada vez son más los chicos que salen de la escuela con un nivel de inglés que les permite comunicarse fluidamente en este idioma, demostrando un nivel B2 e incluso un C1 antes de entrar en la universidad”, señala Bradshaw. Así también lo considera María Perillo, presidenta del consejo educativo en ABA English, para quien las políticas educativas “tendrían que enfocarse más en la práctica comunicativa, y debería haber más iniciativas públicas, como campañas de sensibilización sobre la importancia del inglés para el desarrollo personal y profesional, incluyendo subsidios para cursos y certificaciones”.

Aunque el nivel de inglés no incrementa por sí solo ni los salarios ni el comercio de un país, las fuerzas laborales más eficientes tienden a hablar un mejor inglés (según concluye el mencionado estudio de EF), sin olvidar el impacto positivo que la diversidad en el entorno laboral tiene sobre los resultados de las empresas. “Cada vez hay más necesidad de formar equipos internacionales en cualquier disciplina, para absorber el conocimiento de otros países y conocer otros puntos de vista”, esgrime Perillo.

En cualquier caso, tal y como recuerda Martí, “tu objetivo no es defenderte en inglés; tu objetivo es dominarlo” y, al hacerlo, comunicarte con fluidez. No necesariamente en todos los ámbitos, pero sí en aquellos que más se relacionen con tu actividad laboral o con tus pasiones y aficiones, ya que combinar estas con el aprendizaje del idioma hace que este sea más efectivo.

¿Qué se ha conseguido hasta ahora?

A la hora de juzgar un posible bajo nivel de inglés en España, es necesario tener en cuenta otras consideraciones. Si bien es cierto que el sistema educativo ha estado tradicionalmente centrado en el componente gramatical, también lo es “que ya se han producido numerosos avances hacia metodologías más comunicativas, y el uso de tecnologías en el aula permite romper la barrera del estudio formal, porque los estudiantes más jóvenes se sienten más a gusto trabajando y eso hace que su motivación aumente”, sostiene la responsable de ABA English. Además, el acceso al inglés es mucho más sencillo y generalizado que antes, gracias a la digitalización de la televisión, las distintas oportunidades formativas online y la llegada de las plataformas de streaming.

Por otro lado, y a pesar de las dudas que puedan persistir sobre este tipo de programas, lo cierto es que los programas de enseñanza bilingüe implementados en las distintas Comunidades Autónomas permiten una exposición al idioma mayor y, en muchos casos, más rica y profunda. De entre todos ellos, el de la Comunidad de Madrid (inaugurado en 2004) es el más decano, “y solo es ahora cuando los primeros de esos alumnos están incorporándose al mercado laboral, después de la universidad. Puede que, en los próximos años, se note un cambio en los niveles de inglés, con la llegada de cada vez más alumnos fruto de estas iniciativas en las diferentes regiones”, aventura Bradshaw. Unos programas que, no obstante, “son tan buenos como los profesores que lo imparten”, recuerda Martí, “lo que también ha llevado a zonas de educación bilingüe con un mal profesorado, y entonces no es suficiente. Por eso es tan importante que al profesorado se le apoye, se le forme y se le cuide”.

Las universidades, por su parte, también están tomando medidas para mejorar la internacionalización de sus estudios. Así, gracias al programa Erasmus y otras iniciativas, los estudiantes tienen mejores oportunidades de estudiar en el extranjero durante sus estudios de grado, en muchos casos empleando el inglés como lengua vehicular tanto en su vida cotidiana como académica.

¿Y qué ocurre con las empresas? “Creo que muchas de ellas ya toman un papel activo en la formación de sus empleados en inglés”, cuenta Bradshaw, si bien “donde podrían mejorar algunas es en la dirección dada a la formación: suelen ofrecer oportunidades para estudiar inglés, pero sin centrarse necesariamente en objetivos claros para cada empleado, basados en las necesidades de comunicación que tiene su papel en la organización”. Workplace English Tool es una herramienta desarrollada por la Universidad de Cambridge para identificar los niveles lingüísticos que necesitan los empleados en cada destreza para realizar su trabajo.

¿Cómo es una buena metodología de aprendizaje del inglés?

“Existe un orden natural de adquisición de las competencias de un idioma”, explica Perillo. “Primero hay que escuchar y comprender; luego hablar; y, a continuación, leer y escribir. Los niños aprenden escuchando e imitando, y también los adultos que van al extranjero a vivir una inmersión lingüística. Eso significa que el punto de partida para el aprendizaje es la escucha, y no la gramática o la lectura”. Muchas veces, añade, hacemos lo contrario, y eso nos lleva a tener unas competencias muy desequilibradas: podemos comprender textos escritos, por ejemplo, pero no hablar con fluidez.

En el mismo sentido se expresa el responsable de Cambridge University Press & Assessment en España: cualquier metodología debe centrarse en el uso del idioma para comunicarse en situaciones reales, “sin preocuparse, al menos en un principio, de la perfección con que se dice”. Si se tienen en consideración los niveles establecidos por el Marco Común Europeo de Referencia (MCER), en los niveles inferiores la comunicación siempre será imperfecta, y será el alumno quien deba ir limando dichas imperfecciones según vaya avanzando en el aprendizaje de la lengua.

Consejos para mejorar el inglés en el día a día

Vivir en un entorno de inmersión en el idioma que se quiere aprender es, sin duda, la opción que arroja mejores resultados de aprendizaje. Sin embargo, para una inmensa mayoría de alumnos, esta posibilidad se antoja imposible, ya sea por sus propias circunstancias personales, familiares o profesionales. Por eso Martí, Bradshaw y Perillo, los expertos consultados para este reportaje, recomiendan una serie de pasos que pueden darse para mejorar el inglés sin tener que renunciar a ninguna de nuestras obligaciones cotidianas:

- Planifica tus objetivos de aprendizaje, y mide tu progreso cada cierto tiempo.

- Dedica al menos 20 minutos diarios a ver una película, leer algo, cantar, chatear con amigos extranjeros o escuchar un podcast o audiolibro en el idioma que quieres aprender.

- A lo largo del año, trata de salir al extranjero al menos una semana o dos, para exponerte a una inmersión total.

- Mantente constante: se aprende más dedicando poco tiempo de forma frecuente y regular que dándote atracones ocasionales espaciados por largos periodos de inactividad.

- Empieza un cuaderno de vocabulario lo bastante pequeño como para llevarlo contigo, y cuando tengas momentos libres repasa las palabras incluidas. No hace falta que las memorices, solo reléelas.

- Hay muchas apps que pueden ayudarte: desde Duolingo hasta otras como Write and Improve o Speak and Improve (esta aún en beta) de Cambridge.

- Busca un compañero de estudios para compartir progresos y motivaros mutuamente.

- Grábate de vez en cuando para autoevaluar tu progreso.

- No te obsesiones con la gramática.

Thursday, February 29, 2024

By the Light of the Arrivals Gate

By Nicole Gerber

Guinea's electricity crisis is a metaphor for the country's postcolonial maladies.

For more than a decade, night-time arrivals at Gbessia International Airport in Conakry, Guinea, were greeted by dozens and sometimes hundreds of secondary school students studying in the parking lot. A foreign visitor’s bemusement would quickly evaporate, however, as they noticed that beyond the bright lights of the partially French-owned and operated airport, block after block of the city of two million people was completely dark. Without electricity at home and needing to study page upon page of handwritten lecture notes, many young Guineans made nightly pilgrimages to public spaces, such as the airport or hotel parking lots and gas stations where costly diesel generators kept the lights on.

Witnessing this phenomenon inspired film-maker Eva Weber’s documentary Black Out, shot in mid-2011 and released in November 2012 to international acclaim. The film is concise and artfully composed. As a former Conakry resident, I appreciated Weber’s beautiful portrait of this complex city, and that the entire story is told by Guineans, with the sole foreign voices coming from occasional audio clips of news broadcasts.

Beyond simply a “look-at-this-sad-situation” documentary, the story of students driven to succeed in the face of adversity is the starting point from which Weber subtly explores political and economic dynamics in Guinea.

It is certainly refreshing in a documentary on the challenges of an African country to not have a westerner presenting the narrative. Black Out opens with clips of English-language news broadcasts contextualizing the state of Guinea in early 2011 – having just experienced its first democratic presidential election and struggling to manage competing foreign claims for its vast mineral wealth.

Moving forward, an unobtrusive and serious musical score weaves together interviews and accounts of Guinean secondary students, a teacher, and a worker at Conakry’s main power plant, Tombo, as they discuss their hopes and frustrations about their country’s development. Footage of everyday life in the roundabouts, neighborhoods, and markets of Conakry conveys the city’s bustling commercial atmosphere, which persists despite the challenges of weak infrastructure. This is neither war-torn hellscape nor poverty-stricken desperation, but rather capable, intelligent and ambitious people who feel they are being held back by forces out of their control.

“How does one prepare lessons without light?” the teacher asks, and I feel his pain, having spent many a night in Conakry straining my eyes as I graded papers or planned lessons by the light of a battery-powered lantern. Students read from their notes on topics from microbiology to Carthaginian history, information that must be memorized to pass their French-style school exams, but the terrible inconvenience and danger of staying out until 3am to study is only the beginning. The chronic lack of electricity in Guinea is a symptom of a much larger issue – an economy that struggles to produce formal employment and offers few career opportunities for high-school or university-educated Guineans.

Weber’s critiques the neocolonial economic situation. Train-loads of Guinea’s rust-colored bauxite is shown rolling through the city to the coastal port, where it will be shipped off and turned into aluminum for the profit of foreign-owned companies. “All Guineans understand that Guinea is rich,” the power-plant worker explains, and he is right. The students in Conakry lament that their country’s bauxite, iron-ore, diamond, gold and uranium resources are all being exploited by foreigners, and that poorly negotiated terms by unstable governments have thus far left the Guinean people with nothing to show for it. It is infuriating to hear young men and women proclaim that their best chances for success would be to leave Guinea. Or to hear the school teacher say that he didn’t have a chance to be a respected intellectual because he stayed in Guinea. The unfulfilled promises of politicians are lamented and highlight how domestic and international policy failures reverberate into every aspect of a citizen’s life.

This commentary is what gives Black Out staying power. Conakry’s airport parking lot hasn’t been much of a study hall lately, as a new hydroelectric dam about two hours north of the city has tripled Guinea’s electricity output since 2015. The Kaléta dam cost USD446 million, 75 percent of which was paid for by China International Water and Electric Corporation (CWE), with the state covering the remaining 25 percent. While it has not been a panacea for Guinea’s power problems, there is now electricity in most of Conakry, most of the time, and CWE is now in negotiations with the Guinean government to build another, bigger hydroelectric dam.

The Chinese were not moved by the plight of Conakry’s students to help light-up Guinea, which faced a major economic downturn in 2014 due to the Ebola epidemic and is still struggling to achieve political stability. Chinese banks and corporations have been drastically increasing their investment in Guinea’s bauxite and iron-ore mining operations, including a take-over of Río Tinto’s massive Simandou project last year.

Black Out aired for the first time on American public television recently. Although and the premise of the film no longer exists, the themes continue to be valid. Most students in Conakry can now study at home, but unless growth in the mining sectors fosters more diverse economic development, or the government of newly appointed African Union chair President Alpha Condé can implement policies that create much-needed jobs, Guineans will remain frustrated. (02/06/2017)

The importance of us understanding how algorithms work

By ANJANA SUSARLA, Pledge Times, 13 April, 2021

In the early days of social media, writers and journalists around the world extolled its power as the Arab Spring woke up. Now, in the era of covid-19, experts warn against misinformation about the pandemic or infodemic, which abounds on social networks. What has changed in this decade? How do we now understand the role of social platforms and remain alert to the damage that their algorithms perpetrate?

Networks and digital activism

The networks promised to have better connections and to expand the speed, scale and reach of digital activism. Before they existed, organizations and public figures could use the mass media, such as television, to spread their message to the general public. The media were the filters that allowed information to be disseminated according to established criteria to decide which news was a priority and how it should be delivered. At the same time, citizen communication, among equals, was more informal and fluid. The networks blur the boundaries between the two types and offer the best connected the possibility of being opinion makers.

Twenty years ago there were no media capable of raising awareness and mobilizing for a cause with the speed and scale provided by networks, in which, for example, the #deleteuber label (erase Uber) caused 200,000 accounts to be eliminated in a single day of the transportation application, accused of “thwarting” a strike against Trump’s immigration veto in 2017. Before, for citizen activism to triumph, years of negotiations between companies and activists were necessary. Today, a single tweet can subtract millions of dollars from a company’s stock market value or cause a government to change its policies.

Towards radicalization

While such an opinion-maker role allows for unfettered civic discourse that can be positive for political activism, it also makes people more susceptible to misinformation and manipulation. The algorithms on which social media news updates are based are designed for constant interaction, to achieve maximum engagement. Most major technology platforms operate without the filters that control traditional sources of information. That, together with the large amounts of data that these companies handle, gives them enormous control over how the news reaches users. A study published in the journal Science in 2018 proved that false information on networks spreads faster and reaches more people than real information, often because the news that elicits emotions seduces us more and, therefore, is more likely to be shared and amplified through the algorithms. What we see on our networks, including advertising, is thought based on what we have said we like and our political and religious opinions. Such personalization can have many negative effects on society, such as voter deterrence, misinformation directed at minorities, or advertising targeted on discriminatory criteria. The algorithmic design of Big Tech platforms prioritizes new and micro-directed content, leading to an almost limitless proliferation of misinformation and conspiracy theories. Apple CEO Tim Cook warned in January: “We cannot continue to ignore a theory of technology that says any form of engagement is good.” These models based on participation have as a consequence the radicalization of cyberspace. Networks provide a sense of identity, purpose, and bond. Who publishes conspiracy theories and contributes to misinformation also understands the viral nature of networks, where disturbing content generates more participation.

Coordinated actions in networks can disrupt the collective functioning of society, from financial markets to electoral processes. The danger is that a viral phenomenon, accompanied by the recommendations of algorithms and the resonance box effect of the networks, ends up creating a cycle of filter bubbles that feed back and push users to express increasingly radical ideas.

Let’s educate about algorithms

Rectifying algorithmic biases and providing better information to users would help improve the situation. Some types of misinformation can be solved with a mixture of government regulations and self-regulation to ensure that content is monitored more and misleading information is better identified. To do this, technology companies must agree with the media and use a hybrid of artificial intelligence and detection of false information, with the collective collaboration of users. One way to solve several of these problems would be to use better bias detection strategies and offer more transparency about the algorithm’s recommendations.

But it is also necessary to educate more about networks and algorithms: that users know to what extent the personalization and recommendations designed by big technology configure their information ecosystem, something that most people do not have enough knowledge to understand. Adults who mainly inform themselves through social networks are less aware of politics and current affairs, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center in the US. In the era of covid-19, the World Economic Forum talks about infodemic.

It is important to understand how platforms are deepening the divisions that already existed, with the possibility of causing real damage to users of search engines and social networks. In my research, I have found that depending on how the platforms provide their responses to searches, a more health-savvy user is more likely to receive helpful medical advice from a reputable institution like the Mayo Clinic, while the same search, made by a less informed user, will direct you to pseudo-therapies or misleading medical advice.

Big tech companies have unprecedented social power. Their decisions about what behaviors, words, and accounts to authorize and what not to dominate billions of private interactions, influence public opinion, and affect trust in democratic institutions. It is time to stop seeing these platforms as mere for-profit entities and know that they have a public responsibility. We need to talk about the impact of the ubiquitous algorithms in society and be more aware of the damage that they can cause due to our excessive dependence on big technology.

Anjana Susarla holds the Omura-Saxena Chair in Artificial Intelligence at the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University.

Meet "Generation Mute"

Times of India, April 8th, 2018

Youngsters simply don’t like talking anymore. Texting or using social media is fine. Even an pair of earphones will do, as long as speaking to someone can be avoided. Here’s what a survey from British communications regulator Ofcom revealed. About 15 per cent of 16-24-year-olds don’t want to use their phone to speak to people. They would rather use instant messengers. The same research also said that teenagers would even message people sitting in the same room, at times, next to each other; but not talk to them.

A part of this problem could be because we do not have any shared experience of sound in our digital world. Says Sunaina Mathew, engineer, “We have moved into a noiseless and soundless world, where we hear only our voices and the sound through our earphones buzzing.”

There is a private world of sounds in public spaces. For example, we can sit anywhere, even amid people, but just listen to our favourite playlist. Earlier, we were familiar and accustomed to sounds around us – people talking, the radio playing, children screaming, dogs barking, clang of kitchen utensils, etc. Now, the only sound we hear is the one we choose to, through our earphones. We go to silent discos, listen to music on earphones, have conversations on earphones, listen to movies with our headphones on; we have internalised our relationship with sound and made it a very private affair.

Etiquette expert Pria Warrick says for this generation the most natural and casual communication mode is texting, and phone calls are viewed as an ordeal. “Social media have changed how we communicate privately. There was a time when everyone talked for hours on the landline, and that was considered as a relaxation technique at the end of the day — between friends, lovers, parents-children — but now we think twice about violating someone’s space by calling them on the phone,” she says.

There was also a time when birthdays were special occasions when you expected people to call you. But even that has become a textual affair these days. Maira Khanna, 36, doctor, didn’t get any calls on her birthday, but was flooded with text messages. “I missed the sound of people’s voices and the laughter along with the wishes,” she rues. MIT psychologist Sherry Turkle, one of the leading researchers looking into the effects of texting on interpersonal relationships, feels the onslaught of information and time spent with screens is another reason why people are talking less.

Emotional fallout

Psychologist Rachna Khanna Singh tries to throw some light on this phenomenal change in human behaviour in this century that, she says, will have far-reaching consequences on our emotional stratum. “We are conditioned to go for what’s easy because the innumerable choices and distractions in our lives — social media interactions throughout the day, work correspondence, traffic noise et al — have made our minds exhausted and we are seeking silence with a vengeance now,” she says.

On public transport, we have our earphones on, lest someone should look our way, smile, or worse... talk to us. While out socialising, we are more bothered about interacting with people on the virtual world from our smartphones than the ones right in front of us. Digital expert Chetan Deshpande finds this quite funny and gives an interesting pointer. He says, “Being used to smartphones and social media for a while now, we also love editing our thoughts and expressions. Thanks to courtesy readily-available dictionaries and emojis, we have become accustomed to reducing our mistakes, editing every thought and expression, which isn’t possible while talking on the phone. This freaks people out.”

It’s also a scientific fact that anxious people become tongue tied. Now, think about an anxiety-ridden generation, multi-tasking 24x7. No wonder even the thought of picking up a phone to talk has become a terror.

Sound stats

About 15 per cent of 16-24-year-olds don’t want to use their phones to speak to people. They’d rather text. In TIME magazine’s mobility poll, 32 per cent of all respondents said they’d rather communicate by text than phone, even with people they know quite well. This is truer still in the workplace, where communication is between colleagues who are often not friends.