This blog is an online publication of words, sounds, pictures and moving images, launched to increase your exposure to the English language and/or supplement your in-person English course with language structures, challenging new readings, TED talks, trailers, quality videos, thought-provoking posts, reliable news, quotations, food for thought and icon links to related websites or to the cloud.

Monday, November 30, 2020

The Future Was Supposed to Be Better Than This

Sunday, November 29, 2020

The Holidays Must Look Different

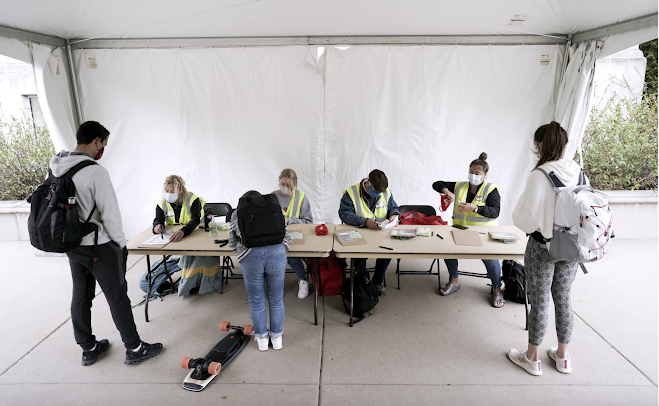

Holidays must look different this year. Lives are at stake. This year’s holiday season will be hard. But shared sacrifice will keep coronavirus outbreaks from spreading further.

In some ways, the coronavirus is still a mystery. Scientists can’t say for certain why it’s deadly or debilitating in some people but has virtually no effect in others. They don’t know exactly how long immunity lasts or whether (or when) a vaccine will stop its spread and bring this wretched chapter to a close.

But they do know this: The virus spreads most rampantly between people who gather indoors, in close quarters, to talk or laugh or sing, without wearing masks. Experts say the wave of outbreaks now sweeping the nation has been caused by precisely these types of gatherings.

As gut-wrenching as this may be, one of the most obvious ways to mitigate further viral spread will be for as many people as possible to stay home this holiday season. Even before the recent spike in cases, scientists knew that holidays were risky business. Memorial Day, the Fourth of July and Labor Day weekend were all followed by measurable spikes in case counts. The fall and winter holidays are likely to be much worse, because they tend to involve more travel and indoor gatherings.

In normal times, some 50 million Americans usually travel at least 50 miles for Thanksgiving dinner, according to AAA and as noted in The Atlantic. This year, especially, the need to draw loved ones close feels urgent, and the idea of sacrificing one more sacred tradition in a year when we have already sacrificed so much feels deeply unfair. But skipping or severely curtailing in-person holiday celebrations now is as much a civic duty and an act of solidarity as wearing a mask in public or standing at least six feet apart.

The coronavirus is surging again, not just in a few hot spots but across the US, with an average of 59,000 new cases per day — as high as that number has been since August. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have labeled indoor gatherings with far-flung relatives as “higher risk” and is advising people to keep these get-togethers as small as possible and to hold them outdoors if they can. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the government’s leading infectious disease control expert, has said that, for safety’s sake, he won’t be seeing his own children this Thanksgiving.

It’s tempting to view the coming holiday season as a well-earned respite from a year filled with hardships. But, as others have argued, those hardships are precisely the point. Children have all but lost a year of schooling, small business owners have seen their livelihoods destroyed, people everywhere have watched loved ones die alone, in nursing homes and hospital wards where restrictions related to Covid-19 prohibited visitors. Failed leadership and failed policy have exacerbated all of these tragedies. Individual or family sacrifices, made for the greater good, have helped.

Taking unnecessary risks now would be an affront to all those sacrifices. What will have been the point of closing schools, hobbling industries or swapping so many human interactions for so many virtual ones? So much of it will have been for naught if a surge of holiday travel gives way to a tsunami of outbreaks and, ultimately, more death.

It’s true that not all gatherings are the same and that individual families can minimize their risks by taking precautions — by keeping gatherings small, by holding them outdoors and by testing and quarantining before and after travel. But those things are all much easier to do for families of means, who are more likely to have spacious, easily ventilated kitchens, space to gather outside, easy access to diagnostic testing and the ability to quarantine.

What’s more, low risk is not the same as no risk, and when it comes to the coronavirus, all risk is ultimately shared. The danger is not individual — it’s collective. The decisions you make are not only about whether you might infect your own grandmother, they’re about whether your family gathering will seed an outbreak that could ultimately infect someone else’s grandmother. The more people gather from far and wide, around densely packed tables, to eat and talk and occasionally shout, the more the coronavirus will spread. That’s an indisputable truth that no amount of wishful thinking or careful planning can undo.

Wednesday, November 25, 2020

The Walk

Little Amal, a young refugee, embarks on a remarkable journey – an epic voyage that will take her across Turkey, across Europe. To find her mother. To get back to school. To start a new life. Will the world let her? Can she achieve what now seems more impossible than ever?

In 2021, from the Syria-Turkey border all the way to the UK, The Walk will bring together celebrated artists, major cultural institutions, community groups and humanitarian organizations to create one of the most innovative and adventurous public artworks ever attempted.

At the heart of The Walk is ‘Little Amal’, a 3.5-metre-tall puppet of a young refugee girl, created by the acclaimed Handspring Puppet Company. Representing all displaced children, many separated from their families, Little Amal will travel over 8,000km embodying the urgent message “Don’t forget about us”.

At this time of unprecedented global change, The Walk is an extraordinary artistic response: a cultural odyssey transcending borders, politics and language to tell a new story of shared humanity – and to ensure the world doesn’t forget the millions of displaced children, each with their own story, who are more vulnerable than ever during the global pandemic.

Saturday, November 14, 2020

Monday, November 09, 2020

Saturday, November 07, 2020

Pop Singer Is Still Missing Amid Chechnya’s ‘Gay Purge’

Human rights activists are demanding answers on the three-year anniversary of the disappearance of Zelimkhan Bakaev, a high-profile pop singer from the Russian region of Chechnya.

In April 2017, the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta alleged that Chechen officials were arresting and violently torturing men they believed to be gay in what was described as a “gay purge”.

“There is little doubt he was targeted because of his sexual orientation,” the group said. Chechen singer Zelimkhan Bakaev was last seen on August 8 in the Chechen capital of Grozny, and Human Rights Watch said his family had been unable to get answers from authorities about what happened to him.

Chechen authorities have repeatedly denied the violent campaign against the country’s LGBT community, but last month a 30-year-old Russian man became the first to publicly identify himself as a victim.

Maxim Lapunov said he was living and working in the Chechen capital of Grozny when he was jailed and tortured by police in March.

Human Rights Watch’s Tanya Lokshina said at the time Lapunov was “incredibly brave and courageous” and other victims hadn’t come forward because of the risk of violent retribution from their families.

The Russian LGBT Network said last month the persecution of the region’s gay people was continuing despite global outcry.“Russian authorities at different levels made numerous statements about the fact that not a single victim filed an official complaint and that made it easy for officials to dismiss the [reports] as rumours,” she said.

They said since March this year more than 150 people had contacted them for assistance, 79 had fled Chechnya and 53 people had found safety outside of Russia.

Reports have emerged claiming that pop singer Zelimkhan Bakaev has become the latest victim of Chechnya’s anti-gay purge. The singer, aged 25, reportedly went missing in August 2017, and hasn't been heard from since by his family and friends. After fears began to grow for his safety, LGBT human rights groups previously thought that Bakaev had been detained. However, sources now believe the Russian singer was brutally tortured to death by authorities shortly after his arrival into the country because of his sexuality.

Chechnya's Islamic, anti-gay leader has denied involvement in the disappearance of Russian pop singer Zelimkhan Bakaev.

The singer was feared to be a victim of Chechnya's anti-gay purge after he went missing in August 2017 while visiting the country for his sister's wedding.

While Chechen officials kept quiet about the disappearance, Ramzan Kadyrov has now claimed that the singer was 'dealt with' by family members.

In a speech to an audience of uniformed security men that aired on state television channel Grozny TV, President Kadyrov denied involvement and claimed the singer's parents were blaming him for the disappearance.

Chechnya's Islamic, anti-gay leader has denied involvement in the disappearance of Russian pop singer Zelimkhan Bakaev.

The singer was feared to be a victim of Chechnya's anti-gay purge after he went missing in August 2017 while visiting the country for his sister's wedding.

While Chechen officials kept quiet about the disappearance, Ramzan Kadyrov has now claimed that the singer was 'dealt with' by family members.

In a speech to an audience of uniformed security men that aired on state television channel Grozny TV, President Kadyrov denied involvement and claimed the singer's parents were blaming him for the disappearance.